%%{

init: {

'theme': 'base',

'themeVariables': {

'primaryColor': '#9fe1ff',

'primaryTextColor': '#470044',

'primaryBorderColor': '#000000',

'lineColor': '#9158A2',

'secondaryColor': '#e79aff',

'tertiaryColor': '#fffc58'

}

}

}%%

gitGraph

commit id: "a1b2c3d"

Basic git cycle

Learning the basic git cycle

What does git do?

gitallows you to bundle up changes to various files, and give the group of changes a unique commit hash and an explanatory message.gitworks on a project level, so you can make a bunch of changes to different files in a folder, and then commit all those changes with a descriptive message- It’s recorded that you made those changes, and there’s a unique commit hash that you can quote to point at the exact state of your folder when you added those changes.

What does git do?

gitis a command line program- There are actually only a few commands you’ll really use regularly

- But before we move on to learning what commands are needed, let’s try to build a mental model of

git - Hopefully this will be useful to those of you who are already using

gittoo!

What does git do?

Old version of python-file.py

1 # This is a comment

2 import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

3 x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

4 y = [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

5 plt.scatter(x, y)

New version of python-file.py

1 # This is a comment

2 import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

3 import numpy as np

4 x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

5 y = [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

6 plt.scatter(x, y)

6 plt.plot(x, y)

Line 3 added, line 6 removed, line 6 added.

What does git do?

New version of python-file.py

1 # This is a comment

2 import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

3 import numpy as np

4 x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

5 y = [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

6 plt.scatter(x, y)

6 plt.plot(x, y)

Line 3 added, line 6 removed, line 6 added.

Associated git commit

File: python-file.py

Commit hash: u87wy9o2

Commit message: change plotting method

+++ 3 import numpy as np

- – 6 plt.scatter(x, y)

+++ 6 plt.plot(x, y)

What does git do?

- When we work with

git, we bundle up changes in our project folder (/directory) and commit our changes. - Each commit (bundle of changes) gets a unique id - a hexadecimal hash that’s 40 digits long (we’re just going to abbreviate to the first 7)

- The commits are made to a “branch”

What does git do?

- When we work with

git, we bundle up changes in our project folder (/directory) and commit our changes. - Each commit (bundle of changes) gets a unique id - a hexadecimal hash that’s 40 digits long (we’re just going to abbreviate to the first 7)

- The commits are made to a “branch”

%%{

init: {

'theme': 'base',

'themeVariables': {

'primaryColor': '#9fe1ff',

'primaryTextColor': '#470044',

'primaryBorderColor': '#000000',

'lineColor': '#9158A2',

'secondaryColor': '#e79aff',

'tertiaryColor': '#fffc58'

}

}

}%%

gitGraph

commit id: "a1b2c3d"

commit id: "4e5f678"

What does git do?

Figure 1: Git workflow process visualization: each “version” of the project is a commit.

What does git do?

%%{

init: {

'theme': 'base',

'themeVariables': {

'primaryColor': '#9fe1ff',

'primaryTextColor': '#470044',

'primaryBorderColor': '#000000',

'lineColor': '#9158A2',

'secondaryColor': '#e79aff',

'tertiaryColor': '#fffc58'

}

}

}%%

gitGraph

commit id: "a1b2c3d"

- Because each “bundle” of changes has been saved with a unique id, we can roll back our changes to a previous version if we want

What does git do?

%%{

init: {

'theme': 'base',

'themeVariables': {

'primaryColor': '#9fe1ff',

'primaryTextColor': '#470044',

'primaryBorderColor': '#000000',

'lineColor': '#9158A2',

'secondaryColor': '#e79aff',

'tertiaryColor': '#fffc58'

}

}

}%%

gitGraph

commit id: "a1b2c3d"

commit id: "4e5f678"

The git cycle

So we’ve looked at the idea of bundling up changes as commits, but what does that actually involve?

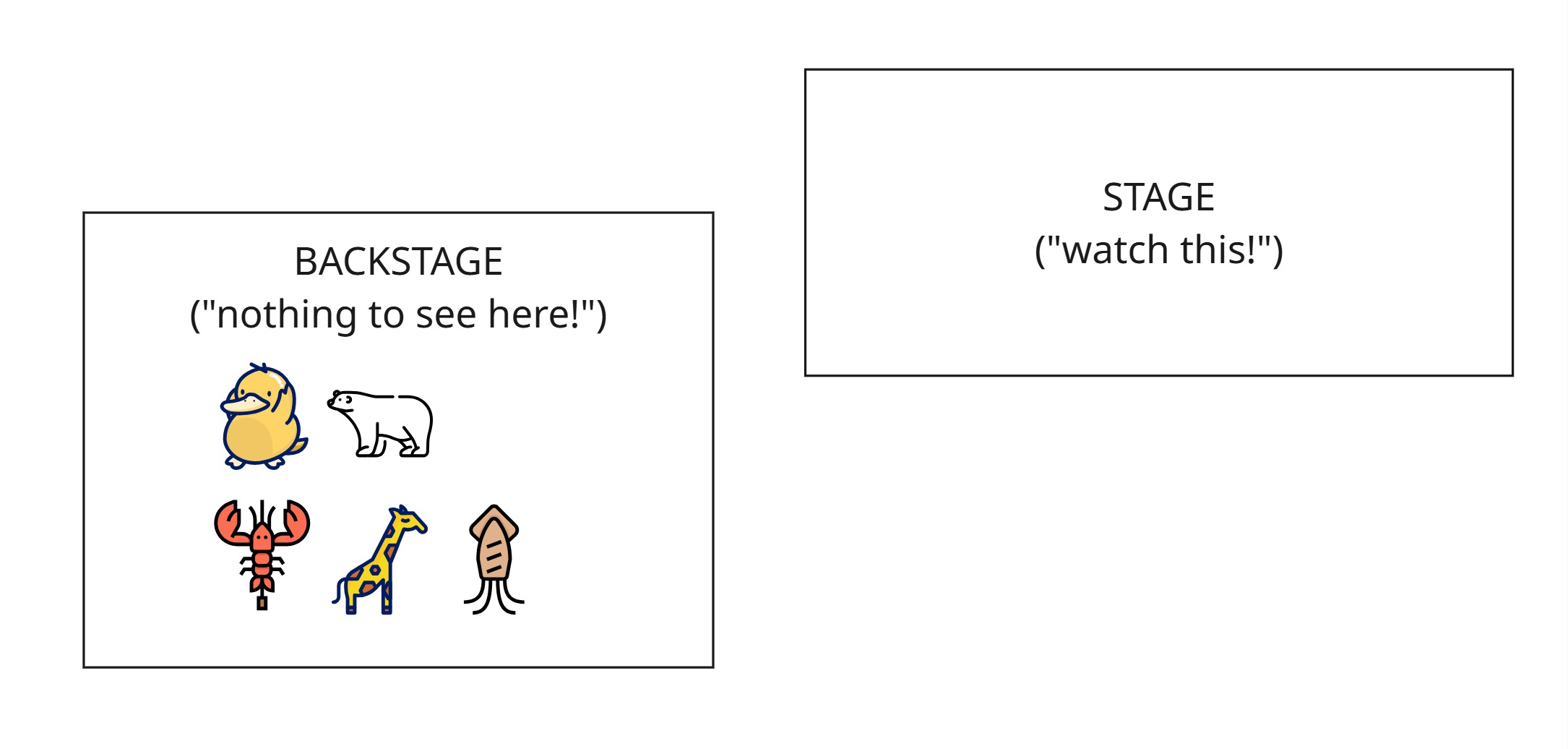

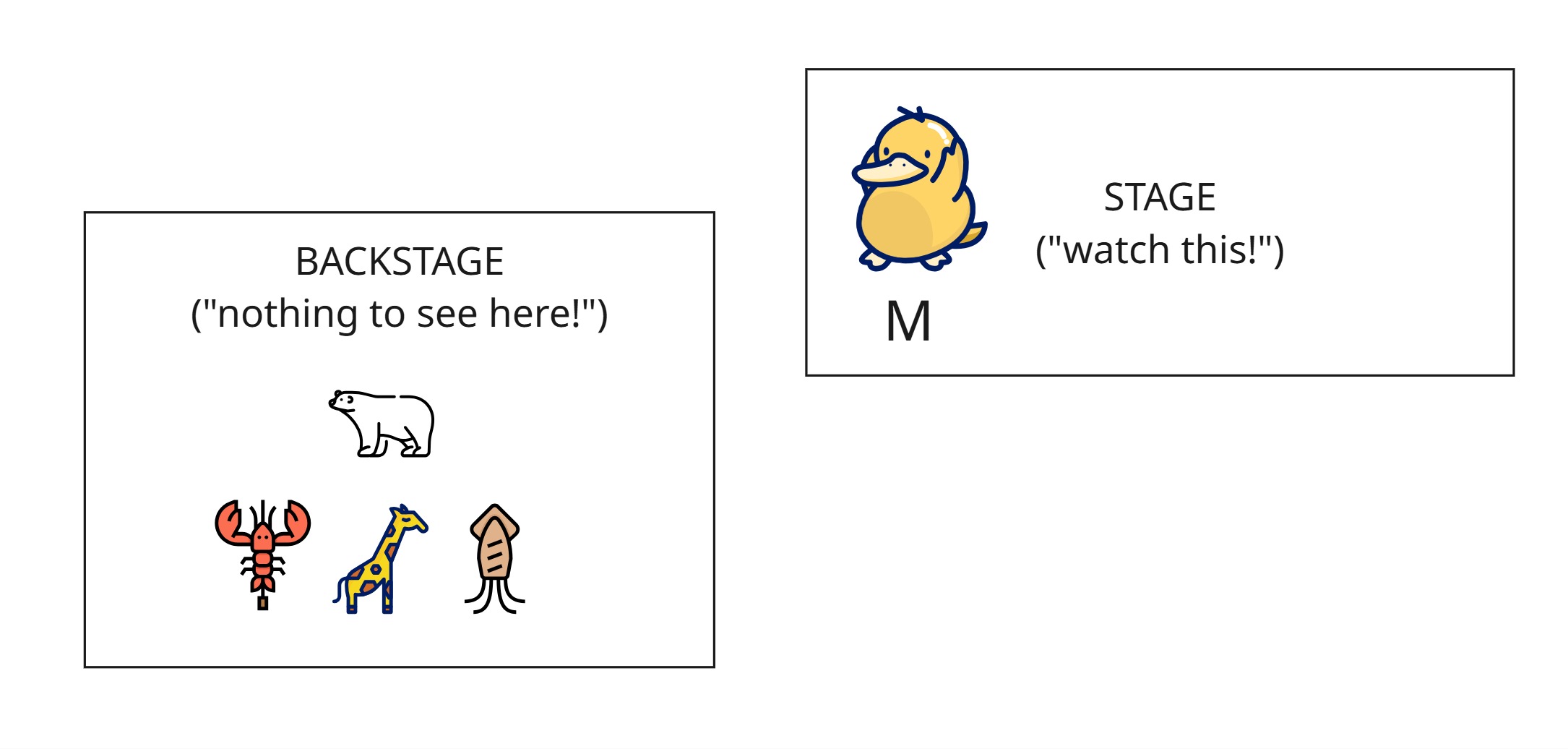

I like to think of a theatre, where the files are the cast waiting in the wings…

Figure 2

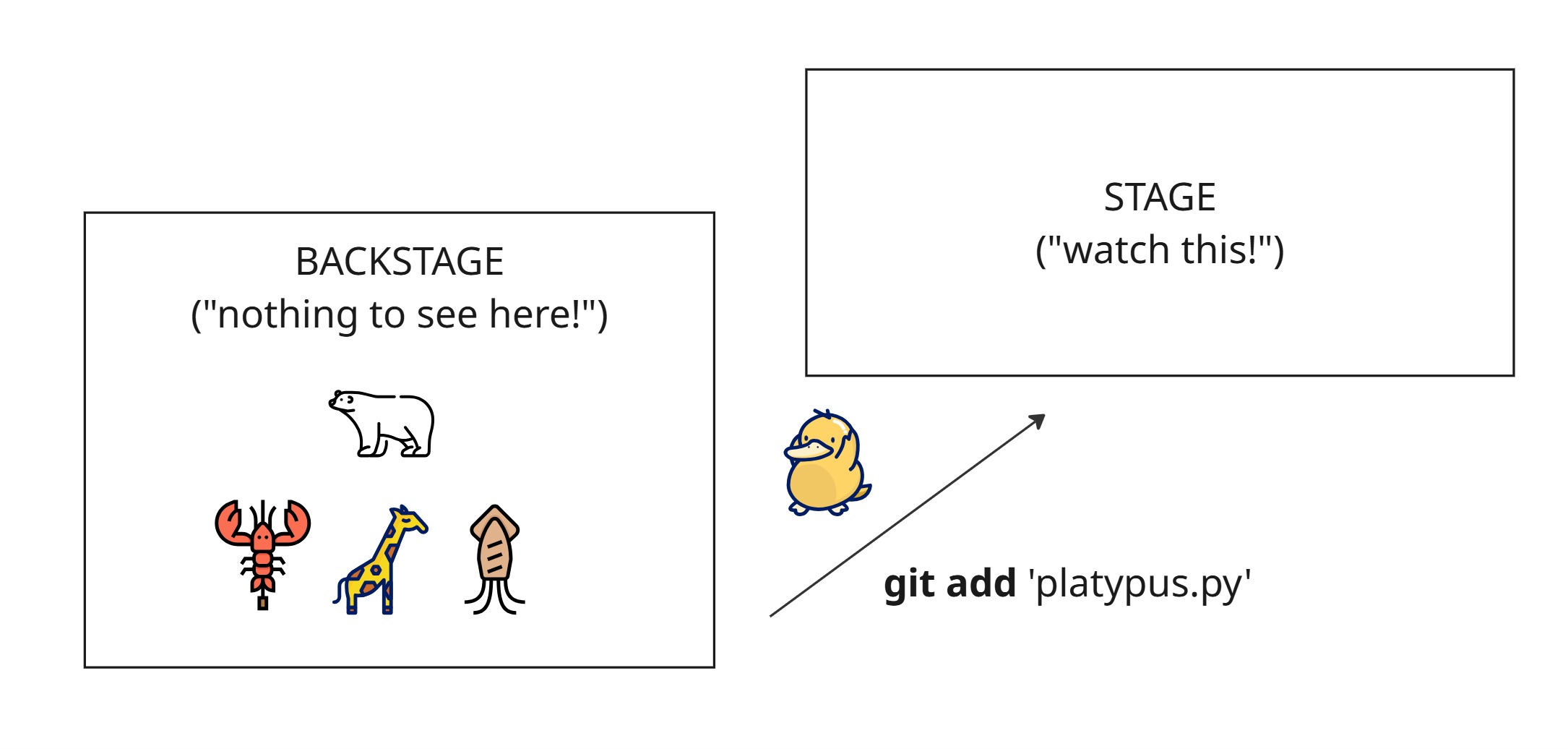

The git cycle: add

git add filename adds a file to the staging area…

Figure 3

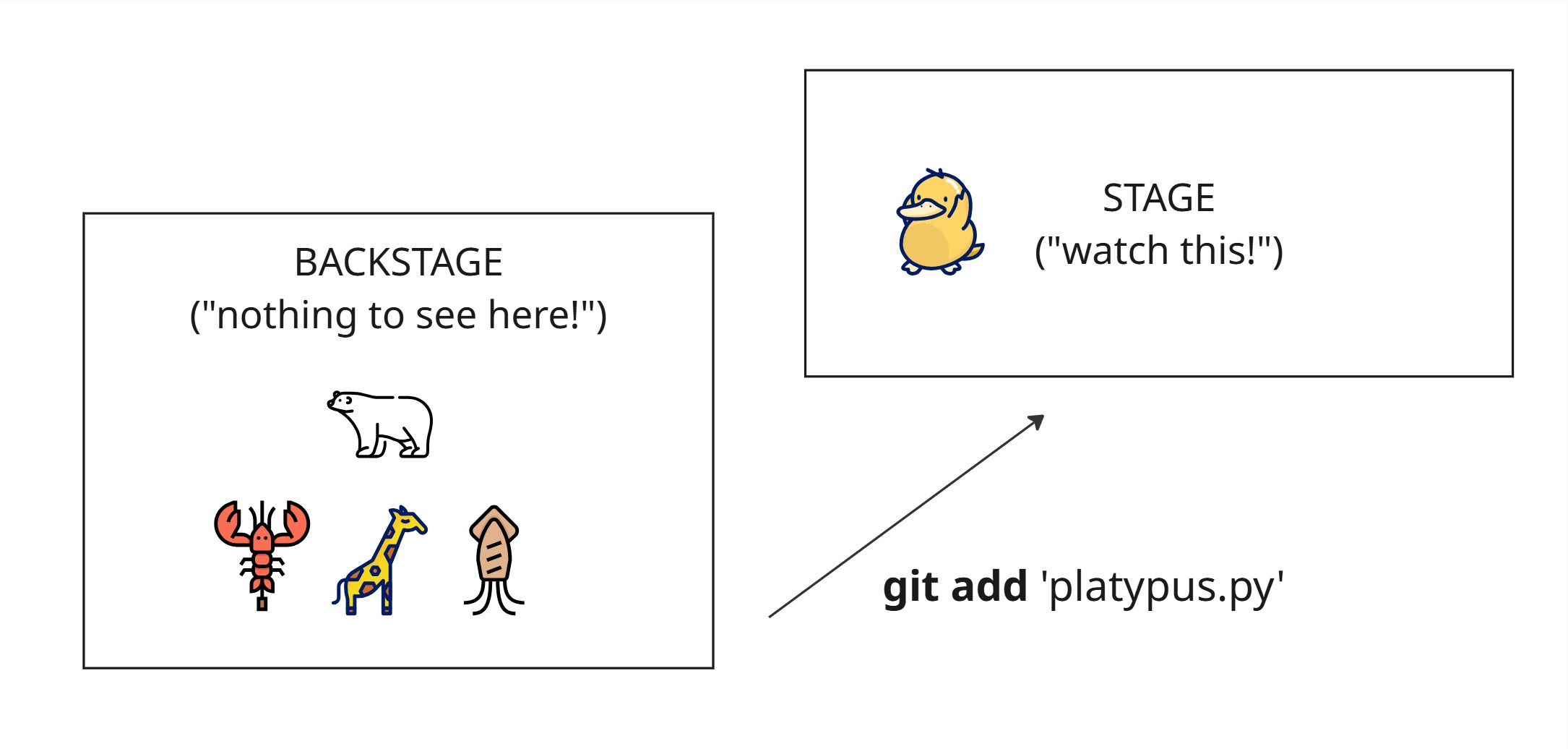

The git cycle: add

It tells git, ‘pay attention to any changes I make to this file’

Figure 4

The git cycle

When a file on the stage is modified, git notices and flags it with ‘M’

Figure 5

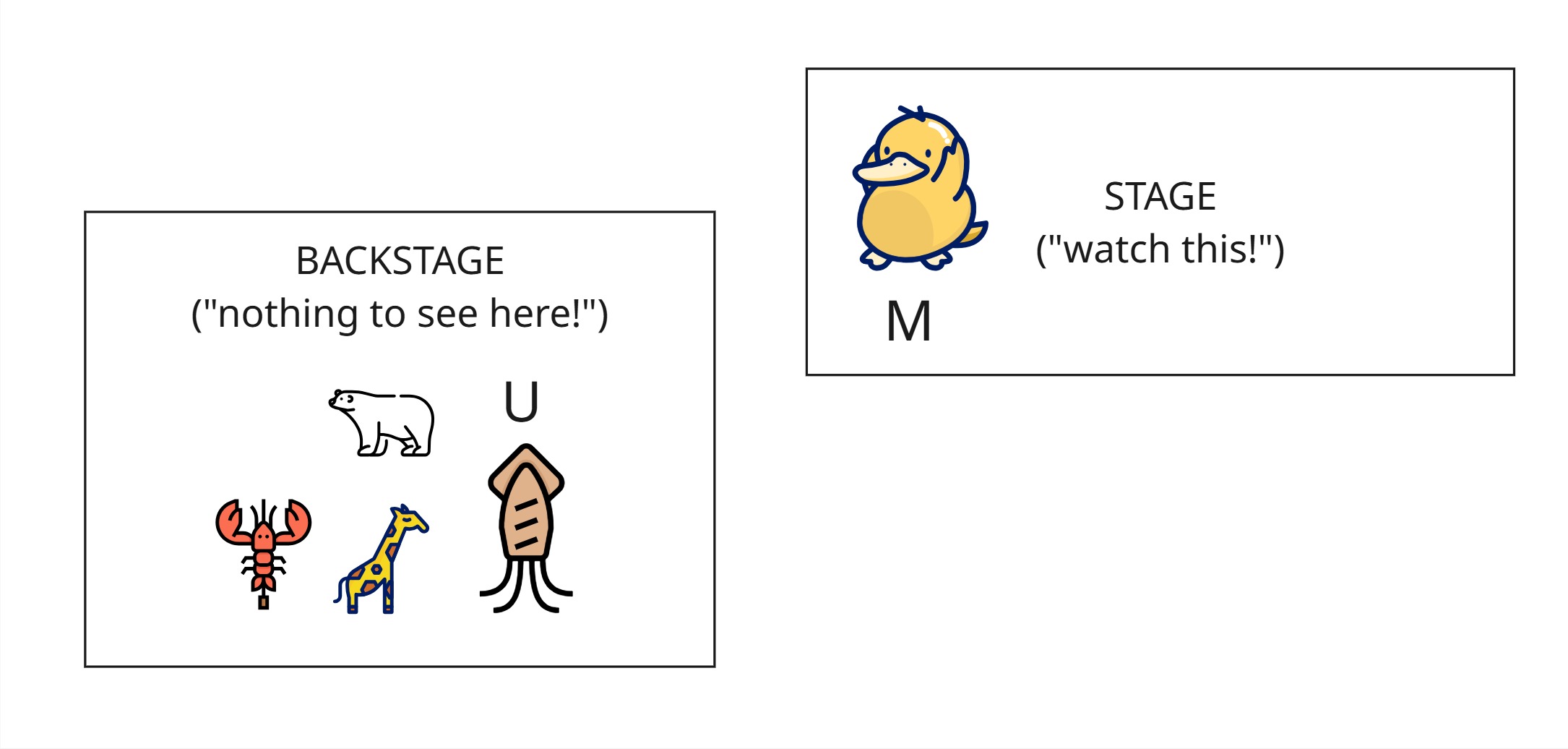

The git cycle

When an unstaged file is added or modified, git notices and flags it with ‘U’

Figure 6

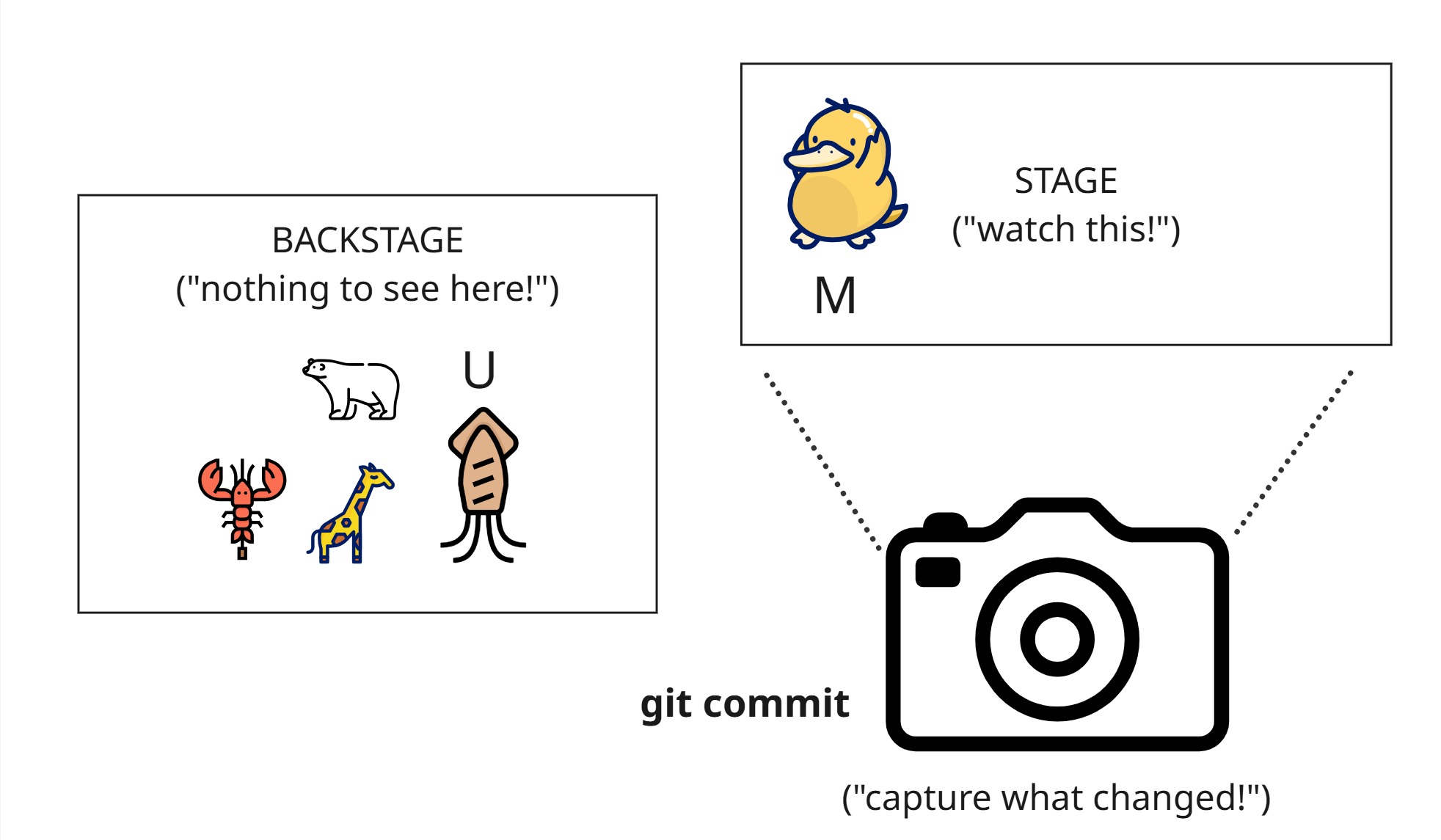

The git cycle: commit

git commit creates a record of the changes in the version history

Figure 7

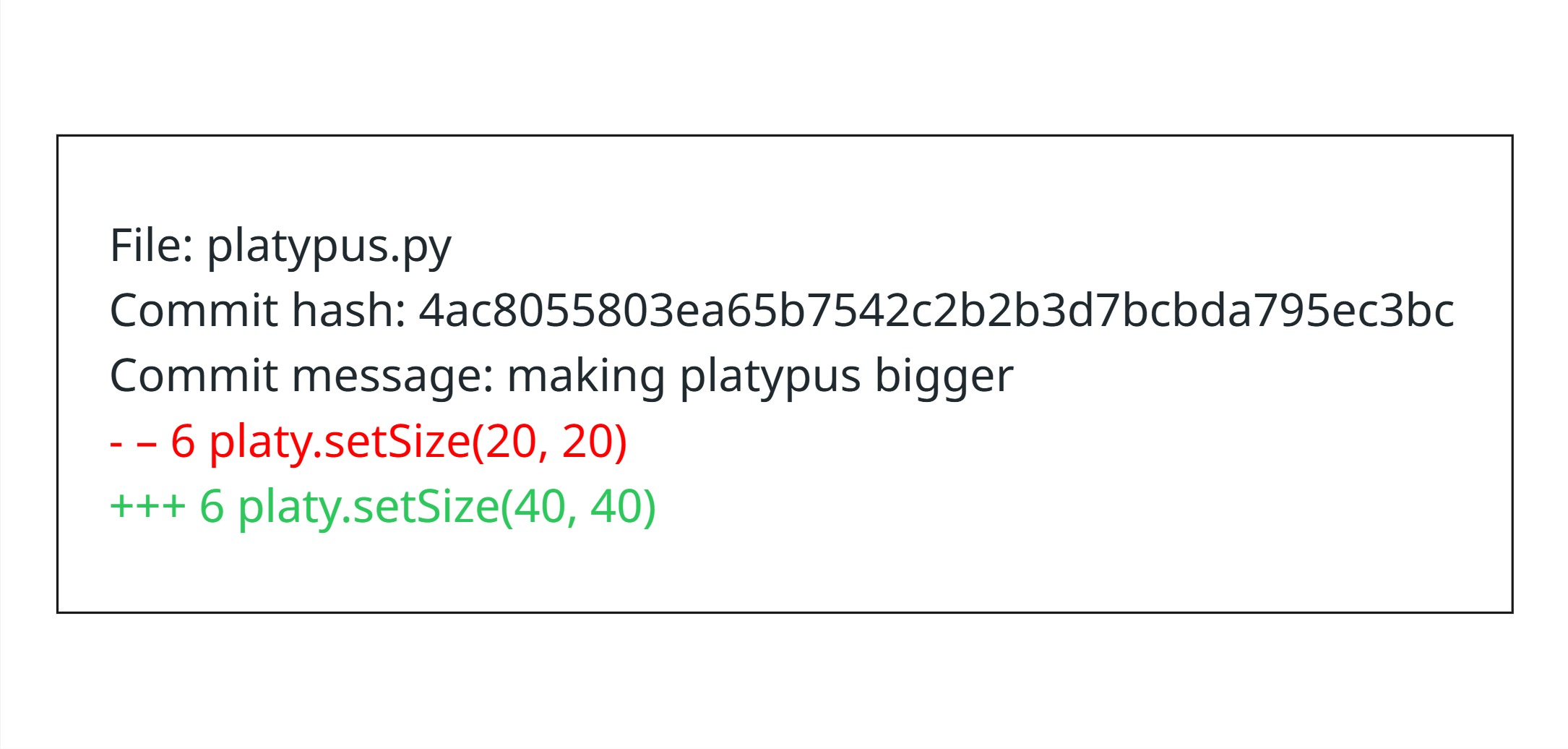

The git cycle: commit

- Each commit can be identified by its unique ID or hash

- A message must be included with each commit, explaining the change

Figure 8

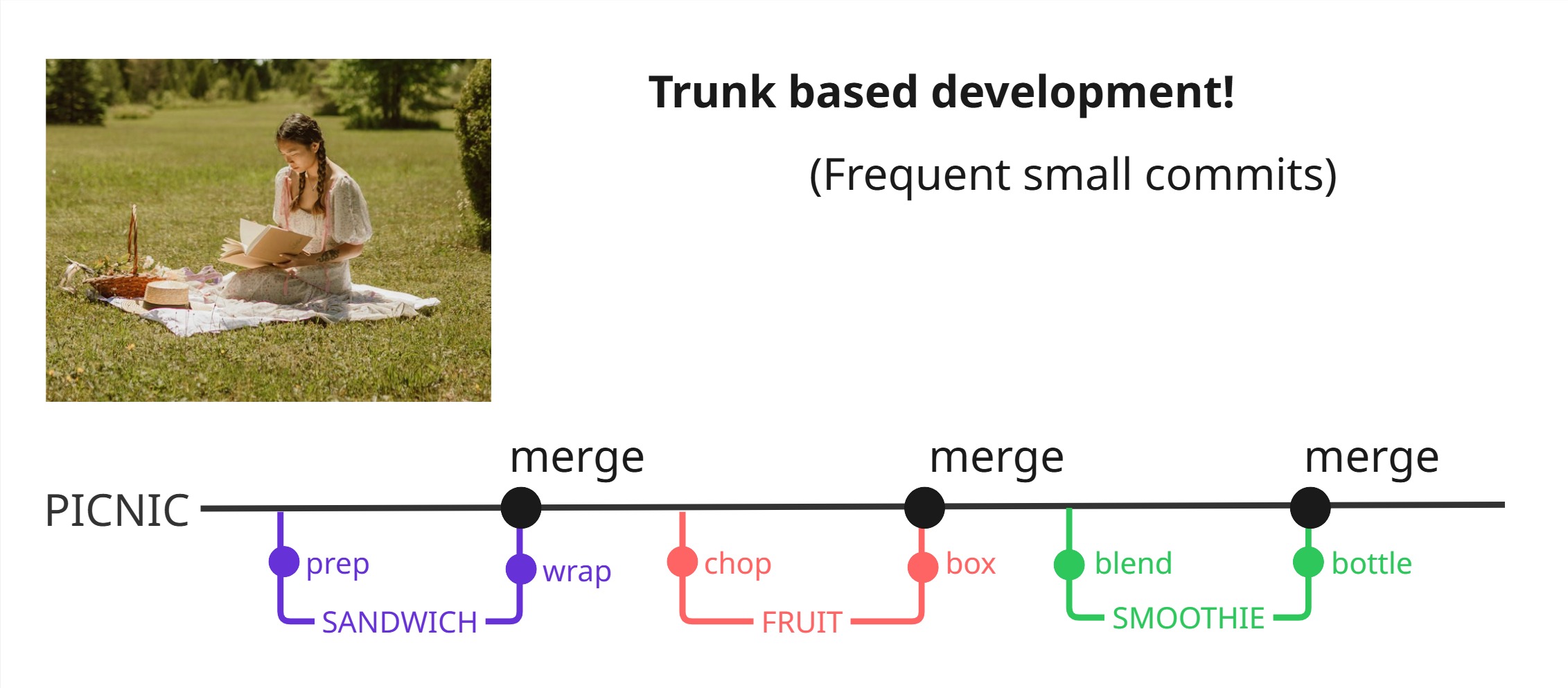

The git cycle: picnic analogy

Maeve likes to think of it like packing a picnic basket:

- I make a sandwich and wrap it up

- I add it to the basket

- I chop up some fruit and put it in a lunchbox

- I add that to the basket

- I make a smoothie and bottle it

- I add that to the basket too

- Finally, I close the picnic basket and secure the latch

The git cycle: picnic analogy

How is it like the git cycle?

- I make a sandwich and wrap it up -> I make some edits to files/create new files in my project folder

- I add it to the basket -> I

addmy changes - I chop up some fruit and put it in a lunchbox -> I make some more edits to files

- I add that to the basket -> I

addmy changes - I make a smoothie and bottle it -> I make some more edits to files

- I add that to the basket too -> I

addmy changes - I close over the top of the picnic basket and secure the latch -> I

commitall these changes that I previouslyadded

The git cycle

create/edit -> add -> commit

%%{

init: {

'theme': 'base',

'themeVariables': {

'primaryColor': '#9fe1ff',

'primaryTextColor': '#470044',

'primaryBorderColor': '#000000',

'lineColor': '#9158A2',

'secondaryColor': '#e79aff',

'tertiaryColor': '#fffc58'

}

}

}%%

flowchart TD

Untracked -->|**git add**| Staged

Staged -->|**git commit**| Committed

Committed -.->|*edit files*| Untracked

- We need to

addeverything to our picnic basket - When we are happy with our bundle of changes, we close up the basket and

committhe changes, and add a nice little label to it in the form of a commit message

The git cycle

Some new jargon - the state of the files in your repository

%%{

init: {

'theme': 'base',

'themeVariables': {

'primaryColor': '#9fe1ff',

'primaryTextColor': '#470044',

'primaryBorderColor': '#000000',

'lineColor': '#9158A2',

'secondaryColor': '#e79aff',

'tertiaryColor': '#fffc58'

}

}

}%%

flowchart TD

Untracked -->|**git add**| Staged

Staged -->|**git commit**| Committed

Committed -.->|*edit files*| Untracked

- Untracked/modified: files that have been created or edited since the last cycle, that haven’t been added or committed

- Staged: files that have been added (put in the basket) but not committed yet.

- Committed: files that have been added and committed and now have a unique id attached to their most recent changes (and have not been edited since the last commit)

As well as being able to “undo” entire commits, you can undo different stages of this cycle (e.g. you can unstage files so they go from being staged to untracked)

Maeve’s mammoth commit

- Maeve’s picnic commit was pretty big!

- What if she wants to remove the fruit without removing the sandwich and smoothie?

- In practice, aim to keep commits small and focused on a specific update or bugfix

Figure 9