Introduction#

This course uses Python to introduce some concepts that are core to producing good data visualisations that can both help you to better understand your results, and to communicate your research findings to a wider audience. As stated in the course blurb, this is an introductory course that focuses on static plots that may be the basis for discussion or for presentation as a figure in a report as opposed to interactive visualisations such as dashboards.

In addition to walking you through some step-by-step advice regarding libraries that are available, and building plot templates that let you save out your figures to high resolution PNGs or PDF files, we are also going to discuss how best to represent your data in a way that is meaningful, aesthetically pleasing, and scientifically robust.

Before introducing the libraries and modules that are available, or the actual step by step of how to create plots using Python, we are going to walk through some of the important considerations when deciding how you are going to visualise your data.

Choosing the type of plot to use to represent your data is not something obvious or straightforward, and is something that will never have a unique solution: there are lots of good options that may win out in certain situations.

In order to structure this discussion a little better, we are going to use the PLOS Computational Biology paper Ten Simple Rules for Better Figures by Rougier, Droettboom and Bourne, 2014. In this section, we provide a modified version of this paper that is tailored towards this course and topics we will be discussing.

Objectives

By the end of this section, you should…

Be able to recognise possible issues with scientific figures and be able to critically evaluate data visualisations

Have a framework to build useful, objective figures to illustrate your results

Have resources to further investigate different aspects of scientific figure making

Ten Simple Rules for Better Figures#

Rougier et al. (2014) state that scientific visualisation—the process of graphically displaying scientific data—is a process that is neither direct nor automatic, and acts as a graphical interface between people and data. They provide ten rules as a guideline to consider whenever you are creating a scientific figure.

Rule 1: Know Your Audience#

One of the key factors to consider when designing a figure is to consider who will be reading it.

Is the figure for yourself or direct collaborators? This may be the case if you are quickly checking if results are expected, are pulling together some notes for a supervisory or team meeting, or have some questions for a collaborator about some recent results.

Is the figure for a scientific publication and so for a broader audience who has technical knowledge but does not know the details of your work specifically?

Are you presenting a talk or a poster at a conference where the audience are mainly experts in your niche field?

Is your audience going to be undergraduate students where the aim is to convey a concept or method with your data as an example, instead of conveying your results specifically?

Is you data visualisation being used in an outreach setting for the general public without any assumed research or field-specific knowledge?

Challenge

For each of the suggested audiences above, discuss different requirements for data visualisation.

Click to reveal some suggestions

When creating quick plots for yourself or direct collaborators, you can probably cut more corners than you normally would, as you already understand your subject area and analysis. However, don’t underestimate how much you can forget in a few short months: making sure your plots are easily readible, with sensible axes labels and titles, will help future you to remember what exactly it is you were trying to do!

When producing a figure for a scientific publication, you need to ensure you haven’t cut any corners, and that all relevant information needed is available for a broader audience to be able to digest your work. Figures in a publication can get away with being a bit more dense as usually the reader spends a bit longer looking at them than the equivalent audience member at a presentation or poster session.

At a conference, the audience may range from quite broad to very niche. In general, conference delegates will have less time to absorb your visualisation than someone reading a scientific article would, so in general they need to be less information-dense. Additionally, you can support the physical figure with description and explanation during the presentation, and so the design can be a little more minimal and less self-contained.

When presenting in a teaching setting, often it is a concept, analysis method, relationship between variables etc. that is being taught, as opposed to presenting results as in a manuscript or at a conference. Additional labels, detailed and clear labels and legends, and reduced datasets can help make these style of visualisations more digestible.

Figures for the general public are often the most difficult to desgin, and should only contain the most essential details of your work. Avoid non-standard chart types, and potentially lean into the possibility of schematics and summary plots.

Rule 2: Identify Your Message#

A figure can express an idea quickly, succinctly, and much more straightforwardly than text can: the old adage “a picture tells a thousand words” is true! However, it is important to know exactly what the message of the figure is, to avoid creating either pointless plots that don’t really tell much, or overly complex plots that try to tell far too much.

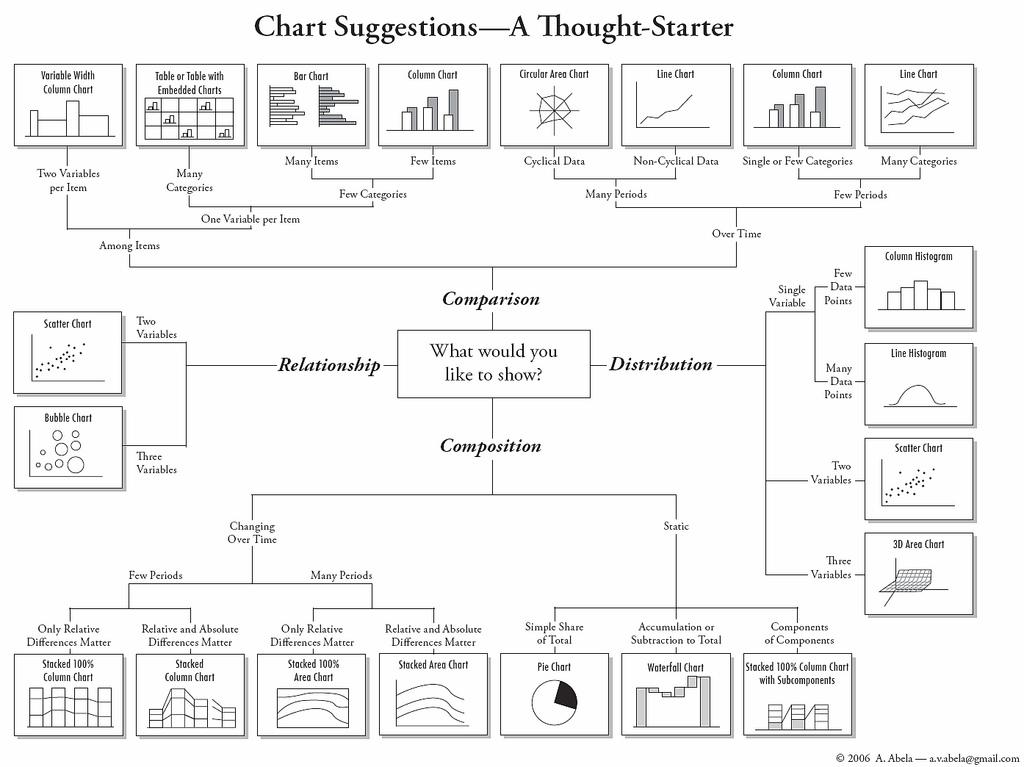

In the same way that you need to decide on the key message for any research paper, and then in more granular detail pick the key message of each subsection of your results, before you start plotting or pick a plot type to represent you data, you need to know what the “take home message” for the audience is. Do you want to show contrast between two different results? Do you want to show evolution through time? Do you want to compare different categories? Do you want to show geospatial variations in data?

Challenge

What plot or figure type have you used most often? Is this the best plot to show your results or might there be a different style of chart that better explains your work?

Rule 3: Adapt the Figure to the Support Medium#

It’s important to understand what medium the graphic or figure will be displayed in: are you preparing for a talk and will be showing your figures over a projector or a shared screen via a webconferencing tool? Will your figures be printed onto a poster for a conference? Will your figure be included in a journal or other publication and will be viewed online where its zoomable?

Figures shown in a presentation will only be visible to the audience for a short amount of time; they will not have time to read lots of labels and annotations, and a detailed and difficult to parse chart will leave the audience confused and will distract them from listening to your presentation. They will also be supported by your discussion points and presentation, so can be less detailed. Figures used in poster presentations will be printed out which can lead to issues in colour grading if screen-specific colourspace is used (e.g. RGB instead of CMYK) and resolution problems if rasterised images are used and not saved at a high enough DPI.

Key points to keep in mind when designing your figure

Size: what size do different components need to be in order to deliver your message in the chosen media? Think about:

Font size for axis labels and annotations

Line thickness

Marker size

Detail(/clutter): in tandem with the choice of size for various plot elements, how visually cluttered is your figure? Readers of a paper may have time to zoom in and read multiple annotations and labels, while audience members at a presentation realistically only have a few seconds to absorb information from a plot.

Colour choices: while colour choice is of course important generally when designing a useful and attractive plot, and in ensuring it is understandable to someone with colourblindness, it becomes especially important when considering where and how your figure is going to be viewed. Certain colours in RGB space cannot be reproduced in CMYK for printing, and so colours used can appear muddied and dull if not appropriately converted. Additionally, different screens and projectors can have different colour settings (e.g. warm light settings) which can make certain colours look more similar to the point of being almost indistinguishable.

Rule 4: Captions Are Not Optional#

Captions are as fundamental to plots as axes labels and legends, and can take different forms depending on the context that the figure is being presented in. In general, a caption provides additional context for the figure, states it’s main message, clarifies and provides further precision, and helps the reader to interpret the figure correctly.

Challenge

Are captions always formal text underneath a figure? How might they be different in a presentation or a poster? Should you adapt captions to suit the medium?

Click to reveal some suggestions

Captions can be different depending on the medium of presentation of the work.

In a paper, a caption is presented as explanatory text alongside the figure.

On a poster, figures may include a paper-like caption, or instead may include related bullet points.

During a talk or presentation, the caption can be thought of as what’s said when the presenter introduces the figure, or may be included alongside as text on the slide.

Rule 5: Do Not Trust the Defaults#

Sometimes the default settings in your chosen plotting software suit your needs entirely: this is more likely to be true if your response to Rule #1: Know Your Audience was “I’m the audience - it’s just me checking my model ran correctly”, or if you have a particular appreciation for small text and garish colour schemes. Font sizes for axis labels, title, tick labels and parameters may be too small to read at the scale you are intending to share this figure.

Rule 6: Use Colour Effectively#

Colour can be an important asset in your scientific visualisations, but it must be used mindfully. According to Edward Tufte 1983, colour can be either your greatest ally or your worst enemy if not used properly (Rougier et al., 2014).

Challenge

What are some uses for colour in your scientific figures?

Click to reveal some suggestions

Adding an additional dimension to your figures; for example a scatterplot where points are coloured according to a third variable. This can cause issues if colour is the only means of distinguishing the variable…

Adding clarity to different marker or line styles: instead of representing a separate variable, colour can work in tandem with other attributes like line-style, for example showing data as a grey solid line and a pink dashed line.

For emphasis! You can colour a specific highlighted datapoint differently from the surrounding data by using a different, contrasting colour to annotate it.

For heatmaps: similarly to the scatterplot answer above, heatmaps can be used to represent a third variable across a parameter space; they are also frequently used for geospatial data such as DEMs.

While colour is a useful tool in your kit, it can also be misused and cause confusion and potentially mislead your audience.

Click to reveal some pitfalls or dangers associated with colour-use

The contrast between two different colour choices might be obvious on your screen/to your eyes, but may be much less obvious with different screen settings/when projected/when printed (see discussion of RGB/CMYK above). Similarly, with various different types of colour vision deficiency (CVD), certain colours can seem very similar to indistinguishable. See this blog post on designing colour-blind-friendly visualizations.

Colour maps may not accurately represent your data; see Crameri et al. (2020).

In general, ensure you have a second method alongside colour to communicate your message:

It is a good practice to, where possible, avoid conveying information purely through color. You should always consider adding other ways to convey the same information besides just color. For example, you might use text, symbols, or patterns.

Further reading on the use of colour:

Rule 7: Do Not Mislead the Reader#

From Rougier et al., 2014:

What distinguishes a scientific figure from other graphical artwork is the presence of data that needs to be shown as objectively as possible. A scientific figure is, by definition, tied to the data (be it an experimental setup, a model, or some results) and if you loosen this tie, you may unintentionally project a different message than intended. However, representing results objectively is not always straightforward. For example, a number of implicit choices made by the library or software you’re using that are meant to be accurate in most situations may also mislead the viewer under certain circumstances. If your software automatically re-scales values, you might obtain an objective representation of the data (because title, labels, and ticks indicate clearly what is actually displayed) that is nonetheless visually misleading.

While we don’t expect to need to spend time explaining that scientific fraud is wrong (and if we do, that’s a larger problem than this data visualisation course can solve!), it’s very useful to highlight the ways you might inadvertently mislead your audience.

Examples of ways visualisations can be misleading:

Using custom baselines for bar charts that skew the appearance of relationships

Using varied scales on x and y axes

Using non-perceptually uniform colourscales (like a rainbow colourmap) that creates false visual contrast between regions (find out more about this in the “Use colour effectively” section).

On the left part of the figure, we represented a series of four values: 30, 20, 15, 10. On the upper left part, we used the disc area to represent the value, while in the bottom part we used the disc radius. Results are visually very different. In the latter case (red circles), the last value (10) appears very small compared to the first one (30), while the ratio between the two values is only 3∶1. On the right part of the figure, we display a series of ten values using the full range for values on the top part (y axis goes from 0 to 100) or a partial range in the bottom part (y axis goes from 80 to 100), and we explicitly did not label the y-axis to enhance the confusion. The visual perception of the two series is totally different. In the top part (black series), we tend to interpret the values as very similar, while in the bottom part, we tend to believe there are significant differences. Even if we had used labels to indicate the actual range, the effect would persist because the bars are the most salient information on these figures. From Rougier et al., 2014 |

Rule 8: Avoid “Chartjunk”#

What is chartjunk? According to Rougier et al., 2014,

Chartjunk refers to all the unnecessary or confusing visual elements found in a figure that do not improve the message (in the best case) or add confusion (in the worst case).

Chartjunk includes (but is not limited to) excessive or distracting use of:

Colours

Annotations

Gridlines

Backgrounds

Arrows

Labels

Different data sets

Legends (with too much detail)

None of the above is inherently a bad thing to include in a figure; however, overloading a figure with too much detail, information or data (in a misguided attempt to adhere to figure limits for publications, slide counts for presentation, or save room on a poster) will just leave your audience feeling overwhelmed and confused.

Think of the chartjunk listed above as accessories with which to adorn yourself and elevate your outfit. Some are requirements that can’t be skipped: legends are like an umbrella on a rainy day; you can’t leave the house without or you’ll regret it, but you probably don’t need two. Ensure you include these key components, like axes labels, that are required to make your figure legible. Everything else is decoration: additional annotations are like a pearl necklace that might in the right context add to the look, but might also start to look a bit overwhelming if you already have jewellery on. Lots of colour and having background fills are a little bit like sequins and large feathers: you want to be very sure you can pull them off before you adorn yourself with them; few people succeed. Do they actually add to the plot or are they more likely to win you a place in a worst-dressed competition?

Here’s a blog that details different types of chartjunk. To be fair, I’ve also included one of my own figures that is distractingly busy, just to reinforce that this is a “do as I say, not as I do” situation, and that sometimes you might crumble and let in some awful design choices. But your next plot can always be better!

Here is a figure I made for a paper Reconciling fast and slow cooling during planetary formation as recorded in the main group pallasites (Murphy Quinlan et al., 2022). Even though I made this figure and did the research behind it, I cannot figure out what it is trying to show without looking at it for way too long. There are too many annotations, arrows, dashed lines and shaded regions. The message gets hidden behind too much chartjunk. Declutter your plots and live a happy, minimalist life! Alt text: A busy, visually cluttered plot, showing overlapping dashed and solid lines, and layers of shaded boxes in the background. Numerous annotations with temperatures and timespans litter the figure. The x-axis reads “Time after magma ocean solidifcation [Myr]”, while the y-axis reads “Temperature at pallasite residence depth [K]”. |

Rule 9: Message Outshines Beauty#

While it is very fair to take pride in the aesthetics of your figures, it is important to remember that the key requirement of a scientific graphic is to communicate scientific results.

Sometimes it is useful to consider figure designs that do not entirely satisfy your design preferences. Situations may include:

Producing a quick plot for yourself to check if results are expected. This plot is just for you and will not be shared or published. It might not be worth sinking lots of time into this, and in this case the default ugly colours and small axes labels might do the trick, instead of sinking time into plotting script you’re going to only use once or twice as part of a process.

If there is a standard or default way of showing information within your field, it might be a good idea to stick with this instead of revolutionising the area and introducing a new way of visualising a standardised data set (unless you want to devote time to this paradigm-shift!). Using a standard, well-known, familiar plot-type can quickly get your audience on-board and have them focus on your results instead of focusing on trying to understand the new groundbreaking figure you’ve designed.

Accessibility! All the above rules deserve to be broken if it increases the accessibility of the figures, because again the key element of any scientific visualisation is to communicate an important message, and you’re excluding a lot of scientists if you make something inaccessible. This includes ensuring font sizes are large and readable, labels are clear, legends are detailed enough that line/point colour are not the only descriminating factor for data, and when necessary, you allow a little bit more “chartjunk” if it improves legibility. Colour-vision related accessibility again should be considered by using colourblind-safe palettes and again not relying solely on colour to differentiate between features.

Rule 10: Get the Right Tool(s)#

What should you be using to plot data? You probably started off with a pencil and ruler on graph-paper, and then transitioned to Excel or another spreadsheet program following this.

While spreadsheet programs such as Excel, Google Sheets, or more scientifically focused programs such as OriginPro can be great for quickly visualising your data, they can take a while to tweak in order to produce a plot to your liking, which can be frustrating if you want to replicate similar plots for lots of different datasets. Of course, you can modify the aesthetic elements of these plots in a graphics package such as Inkscape, Affinity Designer, or CorelDraw; but again this is an inefficient workflow if you have many plots to produce.

That’s where scripting languages come in. In this course, we are using Python and some associated Python libraries including matplotlib and seaborn. Other languages and libraries such as R’s ggplot2 are also commonly used in research settings.